![]()

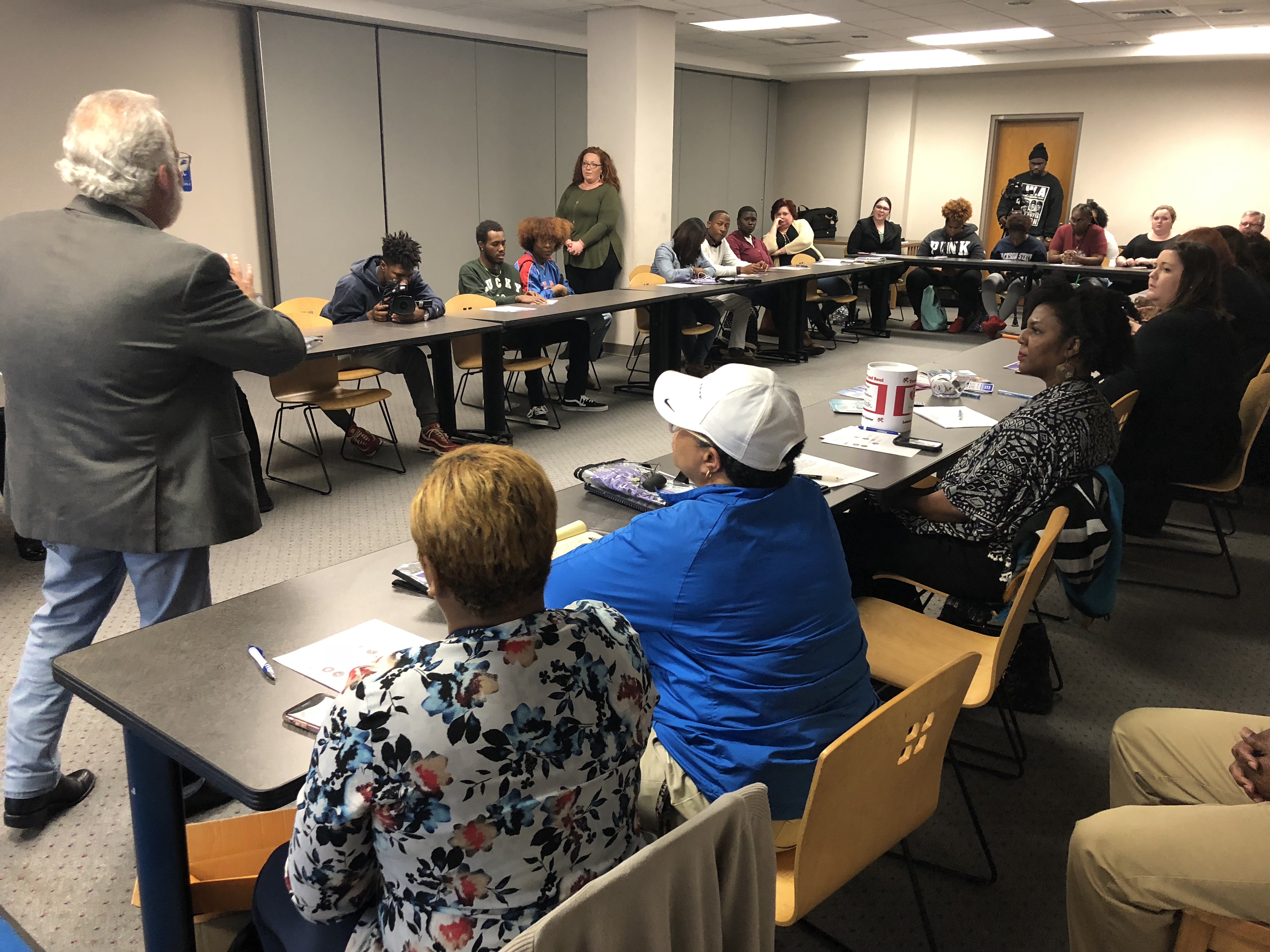

[hr]Amid growing statewide deaths, JSU hosted a town hall meeting recently with several Mississippi agencies raising awareness about opioids. It also included the Latasha Norman Center for Counseling cautioning students about using drugs to get high, socialize or cram for exams.

Although severe addiction is a reality, one medical bright spot suggests opioids isn’t prevalent on JSU’s campus, according to the director of Student Health Services.

Dr. Sam Jones, a longtime physician, said he hasn’t seen a widespread problem among college students ages 18-22. However, he acknowledges that campuses deal with the issue, especially among athletes because of injuries and surgeries.

Jones said opioid use is an expensive habit, thereby limiting college students. He said medical professionals failed to recognize the potency of the drugs and have not been as cautious when prescribing them.

Although he believes firmly that “people don’t abuse drugs; drugs abuse people,” Jones said opioids should be reserved for people who suffer a broken arm or leg, major surgery and certain chronic illness associated with excruciating pain.

Still, Jones said, “At JSU and many other academic institutions in the state, I don’t think we’re finding opioid abuse to be much of a problem in the 18-22 age range.”

Even if the problem is small on JSU’s campus, it still remains a national crisis. For example, in 2017, more people died from drug overdoses than all casualties in the Vietnam and Iraq wars combined.

Those dire statistics reported by the New York Times are just as striking as those shared by Mississippi and federal agencies at the town hall meeting. Several experts, some of who are recovering addicts, sounded the alarm about the epidemic and the resulting overcrowded ERs.

To add further context, they say 72,000 U.S. opioid deaths in 2017 eclipsed the combined number of fatalities from car (30,000) and gunshot (40,000) incidents during the same period.

Shanice White, director and lead therapist for the Latasha Norman center, said her staff has assisted a number of students with substance abuse issues. She said college may be the first time some students witness individuals engaging in drug activity or illegal substances. “Some young people are trying to fit in by experimenting.”

Furthermore, White said, “They don’t realize the consequences of their actions. Some just want to get that sudden rush, instant gratification.”

Even as she cautions against such risky behaviors, she’s optimistic that conversations about opioids will yield positive results.

“A lot of education needs to be shared about the anatomy of the brain and how these potent substances can affect it,” White said.

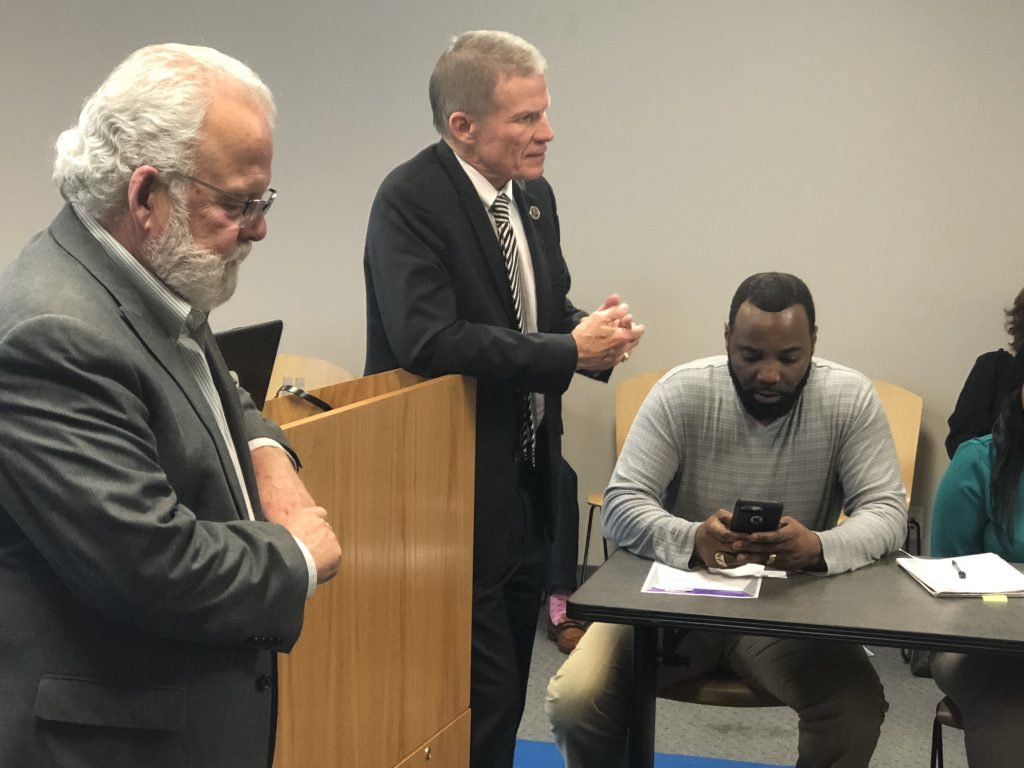

Steve Parker, deputy director of the Mississippi Board of Pharmacy said there is hope for stemming the rising deaths.

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]ARKER said outreach efforts began because there is concern that despite the significant number of deaths the public still doesn’t understand enough about the opioid problem.

“If you want to know what an addicted person looks like, look in the mirror because it crosses every social, economic, racial and ethnic barrier. They can be someone carrying a brief case and putting on a tie every day.” He calls them “functional addicts.”

Parker said agencies are calling on support from families, universities, schools, churches and others. Also, they’ve waged a comprehensive media campaign, “Stand Up Mississippi Against the Opioid Crisis.” The JSU gathering was the 32ndtown-hall meeting in just over a year to spotlight the issue statewide.

Steven Maxwell, deputy director of the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics, said that while the U.S. comprises only five percent of the world’s population, it consumes 80 percent of the opioids manufactured in the entire world. He said 99.7 percent of all hydrocodone products are consumed in the U.S.

Also, Maxwell said 37 percent of young adults don’t even know where to go for help if they or someone they know suffer an overdose.

“Historically, the African-American church has been a place where we can go and receive information.” He’s calling on clergy for assistance. “If we get them educated and onboard, they will help further this message.”

Alarmingly, he said men addicted to opioids are twice as likely to die of suicide than those who are not addicted, and women are eight times more likely to die.

The following group of professionals in Mississippi who are laboring to prevent opioid deaths work in the healthcare, legal, medical, dental and law enforcement sectors:

- Drug Enforcement Administration

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Mississippi Board of Pharmacy

- Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics

- Mississippi Department of Human Services

- Mississippi Department of Mental Health

- Mississippi Department of Public Safety

Angela Mallette is outreach coordinator for the Mississippi Department of Mental Health. Her message focuses on recovery. It’s a subject she knows all too well because she’s struggled with her own addiction to opioids and heroin. She went from “being a professional with a degree and a great career to shooting up heroin. I was at a dangerous place where I didn’t need to be. My family didn’t know what to do.”

Mallette said the first step to take when talking about addiction and recovery is to tell the truth that anyone is susceptible. “It is a disease. Once you cross over into active addiction you can’t string together two rational thoughts to save your life.”

She said recovery is possible by embracing Stand Up’s mantra: “Be Bold. Be Brave. Be Better Together,” Mallette recited.

She said the strategy involves having the courage to address addiction with yourself; being brave enough to share your story with others for support or treatment; and spreading hope to family, church, students and classmates. “As long as that person is still alive, there’s always hope. Every breath is a second chance,” Mallette said.

Mississippi Department of Public Safety commissioner Marshall Fisher calls for more conversation with state leaders, legislators and Congress about funding for mental health and drug rehabilitation treatment inside prisons.

“Opioids affect everyone. It’s been slower affecting the black community, but it’s there,” Fisher said.

He recalls a case in 2011 when he was director of the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics. A 36-year-old African-American female nurse died in a motel off Interstate 55 from a drug overdose on a Sunday morning. In a 14-month period in the metro area, she had visited 38 different medical prescribers, including three oral surgeons, to get drugs.

Because of that woman’s death and the ease of getting prescription medicines, Fisher decided to do something about it. He began pushing for a prescription monitoring program.

“Actually, the program was already out there, but there was no mandate for physicians to use it,” he said. “The point is to get the message out because there’s treatment for people. As bad as the opioid crisis is today, I still don’t think we’ve reached the peak.”

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]EANWHILE, an opioid abuse therapist for Hinds County cautions against spreading misinformation within the African-American communities over the belief that certain drugs don’t impact them.

In recovery himself, JSU alum Jeffery Harvey said, “When human life is at stake it’s everybody’s problem. You have no idea how many African-American people I see who are on opioids, and they don’t even realize that’s what they’re on.” He cited prescription cough syrup with codeine and Lortab pain reliver as examples.

Harvey said he’s shattered by scenes that people don’t see on the evening news such as a three-year-old child sitting outside an emergency room because his parents have overdosed.

Sadly, the toddler’s grandmother is also “strung out on drugs,” he said. His message to the African-American community is that “united we stand, divided we fall.”

Now, Harvey is focused on “selling hope because addiction is real.” Statistically, he said a lot of these opioid numbers involve young people. In 2017, he was slated to counsel only 700 individuals ranging from high school to college. Instead, he ended up working with 6,300.

Because of those sheer numbers, he’s advocating for better prevention efforts in schools. He said when he was young he wanted to be a fireman, a lawyer and a teacher. Instead, he became a drug addict.