![]()

[hr]

Although only seven percent of African-American students today choose HBCUs, several college presidents and a documentary film director told a Jackson State University audience screening “Tell Them We Are Rising” that these institutions must survive.

JSU joined Mississippi Public Broadcasting, Tougaloo College and JSU’s Department of Journalism and Media Studies as sponsors of the powerful documentary about the relevance of HBCUs. It was previewed by more than 100 people Thursday inside the Mississippi e-Center@JSU and will be released nationwide Feb. 19 on PBS stations, including MPB.

The story explores 150 years of African-American history by examining black colleges and universities. Despite smaller enrollment, HBCUs still account for 25 percent of African-American graduates.

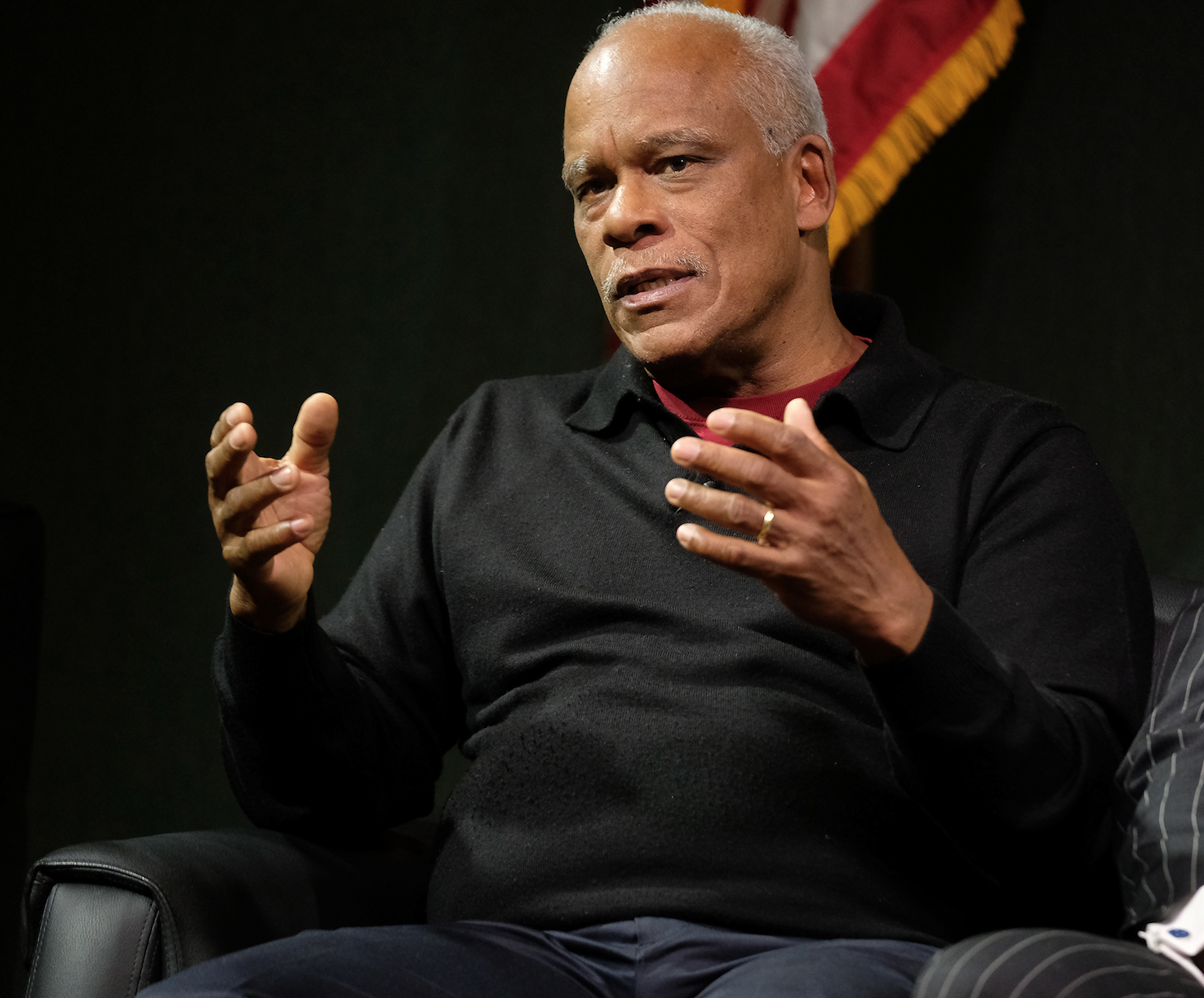

Director Stanley Nelson set out to tell the world HBCUs are still rising. The institutions are credited with building the middle class, paving a path to the American dream and shaping culture. Although it took him 10 years to complete the project, he said it was important to tell this story.

“Furthermore,” said Nelson, “There’s no way my mother and father would have gone to college if it had not been for HBCUs … You will come out of this screening feeling what HBCUs have been and what they are today.”

Nelson’s film begins from the time of enslavement when an education for blacks was forbidden to modern-day history of more than 100 black colleges in the nation.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]E said Southern whites, in particular, feared that educated blacks would unravel their society. The story also reveals that individuals venturing to be educated after the Civil War were killed. Even some abolitionists supporting education were hanged as others helped to set up schools. It’s believed that 20,000 people were slain because of the perceived threat associated with educating blacks – most victims, of course, being African-Americans.

Resistance against white oppressors began to swell and eventually made its way to college campuses over the next several decades. Protests also were leveled against some black university administrators who didn’t appear to sufficiently support the progression of African-Americans.

Clouding America’s violent era of the late 1800s was the 1972 uprising at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where two African-American students were shot in the head. The horrific scene was captured on film and is included in the documentary. It shows law enforcement officers hurling tear gas and unleashing a hail of gunfire on crowds. The deadly aftermath sent shockwaves throughout the nation and beyond.

JSU professor Dr. Rickey Hill, chair of the political science department, was a student activist during the deadly assault. At the time, the junior political science major was vice president of the Student Government Association at Southern. Also, Hill was part of the Black Stone Society, which was labeled by some authority figures as a radical student organization.

Eventually, Hill and other young activists battled with the administration, alleging it “didn’t care for students and faculty and was incompetent.” He said they believed school officials had aligned themselves with outside leadership that controlled the institution.

So, Hill helped stage a monthlong student boycott that brought the campus to a standstill. As a result, a string of events culminated in the deadly attack on their peers. As a young leader rallying for justice, “I did not abdicate responsibility in the loss of lives. We didn’t pull the trigger, but students trusted us on doing the right thing.” He still mourns the loss of his classmates.

Meanwhile, during a panel discussion, JSU President Dr. William B. Bynum Jr. described the documentary as “powerful.” He said he hopes people view the film and learn about the history and struggles of HBCUs.

[dropcap]’I[/dropcap] am convinced that if students see this film they will be more willing to attend HBCUs,” said Bynum, who acknowledged that the institutions face future challenges. He has children who attended an HBCU and realizes that competition for students is “fierce,” especially with white institutions that are better financed.

“We all want each generation to do better than the previous generation so that kids don’t have some of the hardships we faced. There are consequences,” Bynum said. “We’re raising kids who have certain expectations of what an educational experience should be like. Some kids seek certain amenities.” Unfortunately, many HBCUs lack adequate appropriation and support from alumni, he said.

Bynum said the future of HBCUs means “we must meet students where they are, change our pedagogy and the way we instruct.”

Tougaloo President Dr. Beverly Wade Hogan said the film evoked a number of emotions.

“We’re resilient people with all the odds stacked again us. HBCUs have been the launching pad helping Americans create a democracy, getting them involved civically and breaking down barriers,” she said.

Hogan also said HBCUs must do a better job delivering its message. Nevertheless, she urged majority institutions to take note because they will have to “draw from the growing minority population, which will become the largest group of people in the future.” Because of the impending shift in demographics, she said America eventually will realize it can’t sustain itself with an uneducated minority population.

For institutions to thrive, Hogan said, “We must not let the message be that HBCUs are substandard, and we must improve our infrastructure, evaluate academic programs and tell our own story.”

Mississippi Valley State University President Dr. Jerryl Briggs was also part of the panel discussion. He was “overwhelmed” after viewing the documentary. He said the film will help people “understand the importance of where we came from and where we’re going.”

Briggs said the future of HBCUs will require stakeholders to “speak of how we can do more with less.” And, in contrast to other institutions, he said one positive aspect is that HBCUs continue to provide a whopping 25 percent of degrees to African-Americans.

In addition, Briggs said he’s especially proud that HBCUs have role models who let students know “you matter, and you earn an education that matters.”

Like Briggs, even historians in the film praised black schools for being a haven for the best and brightest so they can embrace their full potentials. Commentators also hailed instructors for providing a safety net for faltering students so they eventually would excel.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]URING a Q&A, Briggs also addressed a student wondering how an education can free individuals of enslavement. Briggs said, “We must share wisdom by not withholding knowledge.”

As for Hill, he did not complete his undergraduate degree at Southern University. He and others were expelled and barred. He transferred to Fisk University, which accepted all his credits. Interestingly, he said a college in London that heard about his plight and the campus strife had invited him to enroll. He’s since visited Southern many years later after the tragic events.

For those willing to become activists today, Hill quotes philosopher Frantz Omar Fanon: “Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”

Hill said the young activists only wanted Southern to be “responsive to the people.”

Of his legacy, he said people today don’t blame him or the other students for the events that occurred. Besides the obvious regret over the loss of lives, Hill said the group was successful in helping the university establish a board of trustees, a faculty senate and gave students a voice to help implement policies.

An even greater joy for Hill is that Southern graciously awarded posthumous degrees to the slain students recently.