![]() A daughter of one of the plaintiffs in the landmark 1954 decision Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas told a Jackson State University crowd gathered at the 49thAnnual Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday Convocation on Friday that an element of myth clouds the historic case.

A daughter of one of the plaintiffs in the landmark 1954 decision Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas told a Jackson State University crowd gathered at the 49thAnnual Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday Convocation on Friday that an element of myth clouds the historic case.

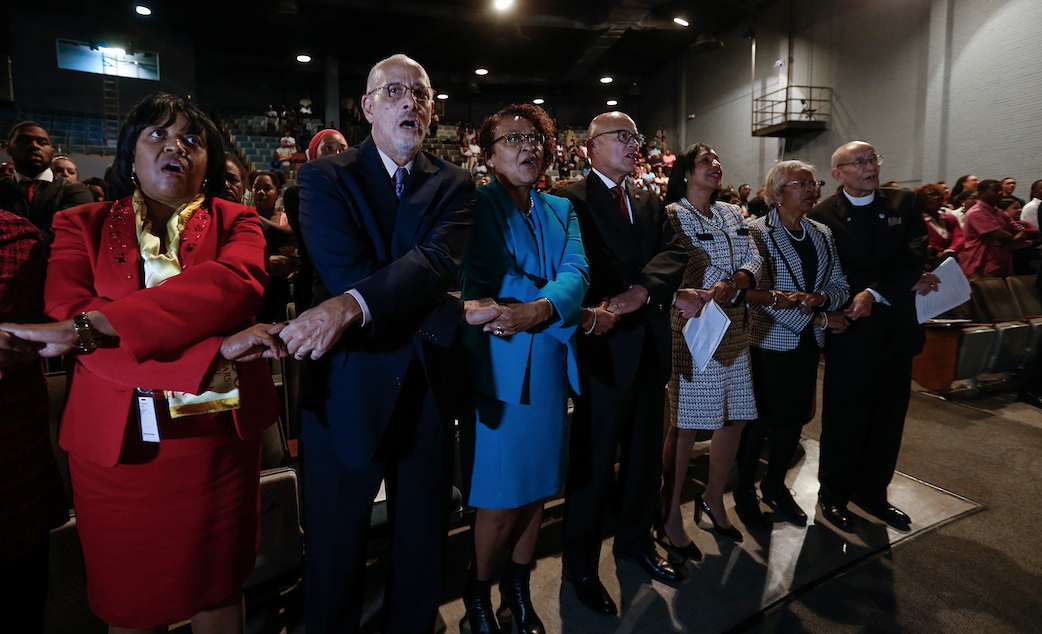

During the celebration inside the Rose E. McCoy Auditorium, keynote speaker Cheryl Brown Henderson proclaimed that the pivotal U.S. Supreme Court case wasn’t about an angry father who sued the school board because his daughter wasn’t allowed to attend a segregated neighborhood school. Describing that account as inaccurate, she admitted, however, during the event sponsored by the Margaret Walker Center at JSU, “that is what most people are going to read in their textbooks.”

[pullquote align=”right”]Blacks and whites had separate proms, separate football and basketball teams, and separate cheerleading squads. Because splitting the groups by race served as an apparent economic, social and superior status for whites, the NAACP launched an attack.[/pullquote]“The truth is so much more compelling,” Brown Henderson said. “My parents were not civil rights activists. They were simply two people with an abiding belief that being United States citizens is not a spectator sport, and when you’re called upon you need to take a stand. So, history and leadership came calling to the two of them.” Brown Henderson, a business owner with an extensive background in education, said her parents and many others were living under the weight of a constitution that had “codified second-class citizenship.” She said they were shouldering the weight of the burden of two Supreme Court decisions.

Brown Henderson said one of those cases was the 1857 Dred Scott decision that declared African-Americans “had no rights that whites were obligated to respect.” The other case was the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision in which the Supreme Court legitimized “separate but equal.”

Ultimately, however, the high court’s decision in the Brown case declared unconstitutional state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students.

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]ROWN Henderson said the Topeka case started after the NAACP tried a 12th time to integrate elementary schools in Kansas – junior high schools and high schools were already integrated for academics. Peculiarly, that didn’t apply to extracurricular activities. For example, blacks and whites had separate proms, separate football and basketball teams, and separate cheerleading squads. Because splitting the groups by race served as an apparent economic, social and superior status for whites, the NAACP launched an attack.

She said her father, the Rev. Oliver L. Brown, was asked to join the roster of plaintiffs when an attorney for the NAACP visited their home requesting his participation. “Little did we know he would end up being the standard-bearer for that case” despite her father not being the lead plaintiff, she said. Among 13 litigants, her father was the lone man in the Topeka case and the 10th plaintiff to sign on. Brown Henderson identified “gender politics” as the only plausible reason that warranted somebody putting her father at the top of the roster.

She noted that Oliver Brown didn’t ask to headline the case. Interestingly, a woman by the name of Darlene Brown (no relation) was a plaintiff, too, but that the 1940s and 1950s were periods during which men were viewed as superior to women. Humorously speaking, Brown Henderson said the belief was that “men used to be all that” in the ’40s and ’50s, but modern times, however, have “straightened out” that misconception. Nevertheless, the Brown case charted a new course for America. Unfortunately, Oliver Brown died in 1961 without knowing the full impact this case would have on the nation.

Dr. Robert Luckett, director of the Walker Center, hailed Brown Henderson for her story in helping people understand the context of the Brown decision and the desires of plaintiffs who simply wanted the best for their children.

Luckett said Friday’s program was also aimed at delivering a powerful message that “history is a living thing, and people are still connected to the movement. … Events like the Martin Luther King Convocation remind us that history is still present. … Nine months after King’s assassination Dr. Margaret Walker Alexander began this convocation at Jackson State, and you can see that legacy coming all the way through to today.”

Luckett said Friday’s program was also aimed at delivering a powerful message that “history is a living thing, and people are still connected to the movement. … Events like the Martin Luther King Convocation remind us that history is still present. … Nine months after King’s assassination Dr. Margaret Walker Alexander began this convocation at Jackson State, and you can see that legacy coming all the way through to today.”

Despite the historic case, Brown Henderson questions whether MLK celebrants are still gathering annually with a greater sense of unity and common purpose. She said despite the past three years having been full of civil rights anniversaries our nation still has “created ambivalence as to the future of race relations.” She blames “heinous acts primarily on the part of law enforcement.”

She said recent observances should be enough to reignite passions of dormant activists or inflame the hearts of future “agents of change.” These include:

2014: The 60th anniversary of Brown vs. the Board of Education; and the 50th anniversary of the 1964 Voting Rights Act

2015: The 50th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery March; the 60th anniversary of the Montgomery Bus Boycott; and the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery

2016: The 50th anniversary of James Meredith’s “March Against Fear” that culminated into a failed attempt to end his life when he was shot three times by a sniper (Meredith is best known for helping to integrate Ole Miss in 1962)

Now, with the 2016 presidential election over, Brown Henderson said Americans are dealing with the realization that we elected someone whose preparation for the Oval Office is in question. She said the final vote “shined a bright light on the roaches of racism – the ones hiding in the corner of the kitchen cabinet of society just waiting for the lights to go on so they could scatter.”

She said even though this is the 21st century, for too many of us it still looks like 1964 because during that year like today “we were talking about racial segregation; and we were talking about black lives matter – the same sentiments on the signs and chants of those in 2014 against the cavalier killings of unarmed African-American people.”

[pullquote align=”right”]“Every time a police officer pulls the trigger and the victim is a person of color with no (firearm) somebody comes forward and says, ‘That’s not who we are.’ It is who we are.” Mississippi helps the country remember “that we have to continue to overcome the way we developed as a nation.” – Cheryl Brown Henderson, keynote speaker[/pullquote]Brown Henderson said she blames the fear of African-Americans for many of the racial crises in the country. She assailed “bigots” for using that as propaganda and “for making someone believe that my son jogging at night is a threat.” Still, she cautioned African-Americans to be “mindful of not making sure we’re making the propaganda somehow a reality. We are not a pathological people; we are people who made this country own up to its founding creed. We’ve given this nation our blood, sweat and tears.”

Brown Henderson especially acknowledged Mississippi in the civil rights struggle, declaring that the state “continues to hold up a mirror to the nation by reminding us constantly of who it really is and what it has overcome.” She said every time a police officer pulls the trigger and the victim is a person of color with no (firearm) somebody comes forward and says, ‘That’s not who we are.’ It is who we are.” She said Mississippi helps the country remember “that we have to continue to overcome the way we developed as a nation.”

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]HE recounted how the Magnolia state elected two U.S. senators during post-Civil War Reconstruction and endured the racial tensions surrounding the martyrdom of state NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers and civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chanay. She then acknowledged last year’s court ruling outlawing segregated schools in Bolivar County after a 50-year battle.

Despite all the turmoil and tragedies, the founding president of the Brown Foundation advised African-Americans in the JSU audience to put their history of self-determination on full display. “We didn’t overcome all of the (racial) challenges of the past by doing nothing. … We took to rebellion in the form of Nat Turner (an enslaved African-American who led other captives to revolt against their white oppressors); and we learned to read in the shadows of a candle late at night. We were not about to let our brilliance, our importance, our beauty be relegated to the brutality of slavery.”

To counter discrimination and misrepresentations, she suggested “marching; writing op-eds to the newspapers about what you think and what’s going on; using social media for good; forming coalitions and being politically active at every level.” Furthermore, she said African-Americans must demand public service accountability while filling membership roles of the NAACP, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and also supporting social justice institutions.

“Remember,” she said, “ ‘We the people’ was never intended to mean we the people of color; we the women; we the disabled; we the Asians; we the LGBTQ community. … The folks who came up with the phrase ‘we the people’ really meant ‘we the land-rich white man’ – never actually anticipating that you all would be sitting here freely at Jackson State University.”

To view photo gallery, click MLK Convocation