![]() [hr][hr]

[hr][hr]

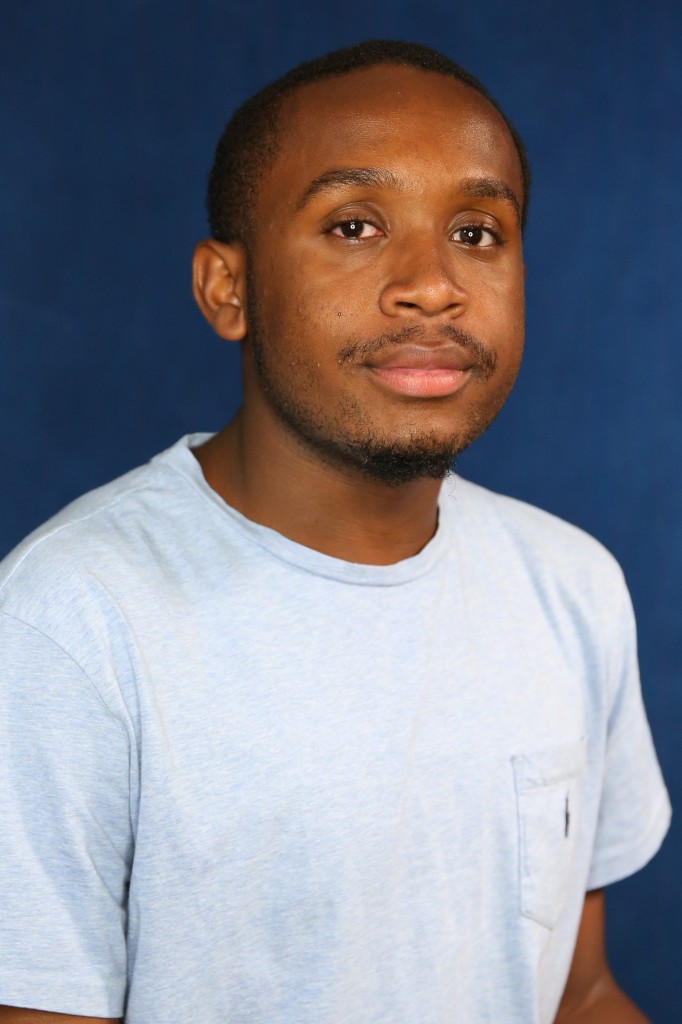

On Jabaris Jefferson’s first day as an intern at Iroquois Springs Summer Camp in Rockhill, New York, he was prepared to turn around and leave.

“It was two hours from New York City. I’m the only African American, so I was quiet, in defense mode, timid, and nervous,” he says.

The JSU senior and criminal justice major questioned if he had chosen the right internship. He planned to pursue corporate law and then become a criminal defense attorney. He also wanted to spend the latter years of his career teaching, which is why he signed up to supervise 8- and 9-year-old-boys for seven weeks at an overnight camp in the southern Catskill Mountains.

However, Jefferson was prepared just in case his ambivalence sent him packing. “I purposely saved enough money in my savings account, so I could say: ‘You know. This isn’t for me. I should go home,”‘ he says. “But they were all so welcoming. They made me feel comfortable.”

The Vicksburg native also discovered that he was not the only African American or person of color working at the camp. He admits that, if he followed his first mind, he would have missed a great opportunity.

Located 90 miles outside of New York, Iroquois Springs is a traditional coed summer camp that has been offering children an extraordinary camp experience since 1931, according to their website. It is owned and directed by Mark and Laura Newfield. The camp advertises that campers “build confidence, independence, resilience and lifelong friendships.”

[dropcap]”We[/dropcap] went through a seven-day training of different seminars before the kids arrived. I learned things like how to handle grief, how to handle peer pressure, and apply an EpiPen if a kid has an allergic reaction,” Jefferson explains. “I had no idea how to use one of those before. Some of the campers had same-gender parents. We learned how to accommodate them and not make them feel uncomfortable.”

He shares that a seminar on child abuse deeply resonated with him. “They taught us how to approach those situations. It made a big difference because ignorance can be hurtful.”

If a child admits to being abused and asks a counselor not to tell anyone, instead of agreeing to keep the secret, promise the child they will be OK or they will receive help, Jefferson explains.

“They taught us safe words and provided better options to use because when you make a promise to a child, you can’t break that promise. Kids remember that,” he says.

The electronics-free policy is another aspect of the camp Jefferson says he enjoyed. All employees were required to put their phones away for the duration of their 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. workday.

“They stressed to us not to use our phones so we could focus on bonding with everyone,” he says. “It was different living with the same people for seven weeks. I made a strong bond with some of them, and I miss them a lot.”

Jefferson says that people should take more phone-free moments. “You get so caught up with what’s going on with social media, outside problems and life. I tell my friends now to turn off their phones and just take a moment.”

Without his phone in tow, Jefferson spent a lot of time at camp playing football, kickball, “bubble” soccer, card games and getting to know his cohort.

“I would recommend that internship to anyone. It’s life-changing,” he says.

Coming from a predominately black institution with friends from the same ethnic background, Jefferson discloses that it was intimidating to walk into a situation where he was one of four African Americans on staff. However, he soon realized that others shared similar sentiments.

“Everyone else was either from another country or New York. I wasn’t the only one who initially felt uncomfortable. There were counselors there from Hungary, Wales, and London, that felt the same way.”

Jefferson says camp owner Mark told him about the diversity training the year-round staff goes through, and the JSU student understood why he felt at ease.

Although Jefferson says it wasn’t always easy sharing a cabin, equipped with bunk beds and two bathrooms, a second counselor and nine campers, he had an amazing time.

A typical day at Iroquois Springs consisted of Jefferson and nine campers participating in a varied schedule of activities. The group would do everything from swimming, archery, and woodworking, to arts and crafts, singing practice, and relay races.

“They had people for everything. Snack was only 20-30 minutes of the day, and they had a lady over snacks,” Jefferson says of Iroquois Springs, which roughly costs $11,000 per child.

There was also a “camp mom” who helped children if they were having a tough time adjusting. Jefferson explains that the “mom” would come around to each cabin and do things like clip the children’s fingernails or read them stories. “It was organized to a tee.”

Jefferson points out one of the main goals of the camp was healthy child development. He then shares that parents would email the camp expressing their shock and awe at how their children spent their time.

“They would say, ‘My kid never goes outside, and you had them outside all summer.’ The parents were moved by what their children had learned,” he says.

Jefferson thanks JSU for the internship opportunity and confesses that his mom, dad, stepdad, and grandmother, went to Alcorn. “So I applied to Jackson State. I didn’t even look at an Alcorn application,” he laughs then admits that he also has a love for his family’s alma mater.

Dr. Etta Morgan, chair of the Department of Criminal Justice, also holds a spot in his heart, says Jefferson.

“When you get to school, sometimes you question if you made the right decision. The Department of Criminal Justice really strives to make sure we graduate with a job or going to graduate school. They make sure we’re headed in the right direction. I appreciate Dr. Morgan and the department a lot.”