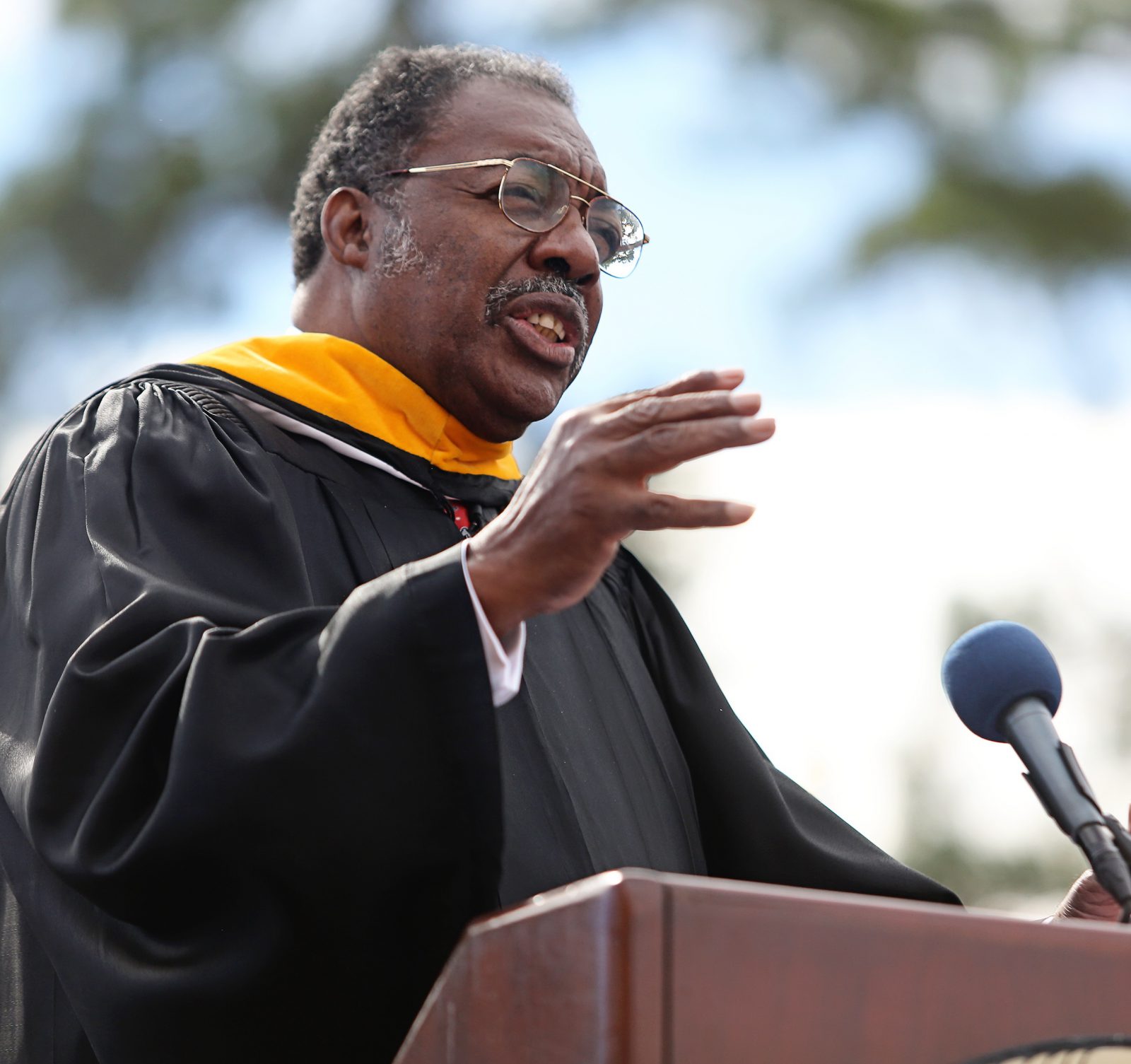

Former Freedom Rider Hank Thomas electrified the audience of the Jackson State University 137th Founders’ Convocation on Thursday, recounting the harrowing events of 53 years ago when he narrowly escaped death.

On May 4, 1961, Thomas said, he was aboard the bus in Anniston, Ala., that was firebombed by Klu Klux Klansmen, attended by a crowd of whites, many of them just out of church and watching with their children on their shoulders.

He described how members of the crowd slashed the tires of the bus so it couldn’t move while still in the station. The bus managed to get out of town, but the flat tires caused it to stop in front of another angry crowd.

The mob smashed the windows because the door was locked and they couldn’t beat those inside. The attackers ultimately threw a firebomb in the back of the bus and then held the front door closed in hopes the freedom riders would burn to death.

But the vehicle’s gas tank ignited and exploded, Thomas said. Some were injured in the blast, but it also created an opening so others could escape. As the fire in the bus raged, Thomas said, someone urged them to lie on the floor since there was oxygen there. He said he believed he was going to die. His choice was to stay in the bus and burn to death or escape through the blast hole and be beaten to death by the mob.

He decided to stay in the bus and die, he said, essentially choosing to commit suicide in the cause of civil rights than to be killed. But they were allowed to leave when state troopers intervened.

But that wasn’t the end of the ordeal. An ambulance came but the white driver refused to take them to the hospital because he was prevented from transporting black people by law. Then-U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy intervened, and they were taken to the hospital with a black driver.

But once at the hospital, they were told that they had to leave and go around the building and enter through the “colored” entrance. Meanwhile, however, the mob had followed them and was threatening to burn down the hospital. They escaped under cover of darkness.

And why did this crowd do this? Thomas asked. They did it to stop black men and women from being able to be treated equally, to be able to vote, to exercise basic rights.

In 1965, Thomas was a medic in Vietnam. He was wounded on the battlefield and two others in his unit were killed.

“The North Vietnamese soldier who shot me could come to Jackson, Miss., and enjoy the rights that I could not,” Thomas said. As for himself, Thomas said he could not vote, could not get a hotel room, could not sit down in a restaurant, but he was on a battlefield wounded and bleeding for his country.

“I am the history, the pain and the joy of my people,” Thomas said.

“I fought for the right to be called a man.”

He added that he is “proud to be an American,” though he has a “rap sheet” of 22 arrests in the cause of civil rights and, hence, is “a career criminal.” And he spoke passionately about President Barack Obama, the first black U.S. president.

But Thomas also warned against prejudice in any form, saying that of the 426 Freedom Riders who came to Jackson, 50 percent were white and 60 percent of the whites were Jewish. “Jews were with us in our greatest hour of need,” he said, adding, if any in attendance should hear of a slur toward Jews to say: “Shame on you!”

Today, the struggle for equal rights includes all races, genders, sexual preferences. It includes keeping voting rights fair and without restriction, rights for immigrants, and for young black men, he said, who want to hear rap music “and not be labeled a gangster and killed.”

Today, Thomas is the only one of the seven original Freedom Riders on the Anniston bus who is still alive.

Thomas said that when he was in Mississippi 53 years ago and he was arrested in Jackson that the warden at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman “didn’t give me any love.”

Dr. James C. Renick, provost and senior vice president for academic and student affairs, called Thomas “a true profile in courage.”

Saying “every great event in our lives requires courage,” Renick asked how many young people today had the courage to do as Thomas had done?

But Thomas’s courageous act, Renick said, was also an act of love — love for freedom, love for America’s ideals, love for his people.

Jackson State University on Thursday gave Thomas a lot of “love” with a standing ovation.