![]()

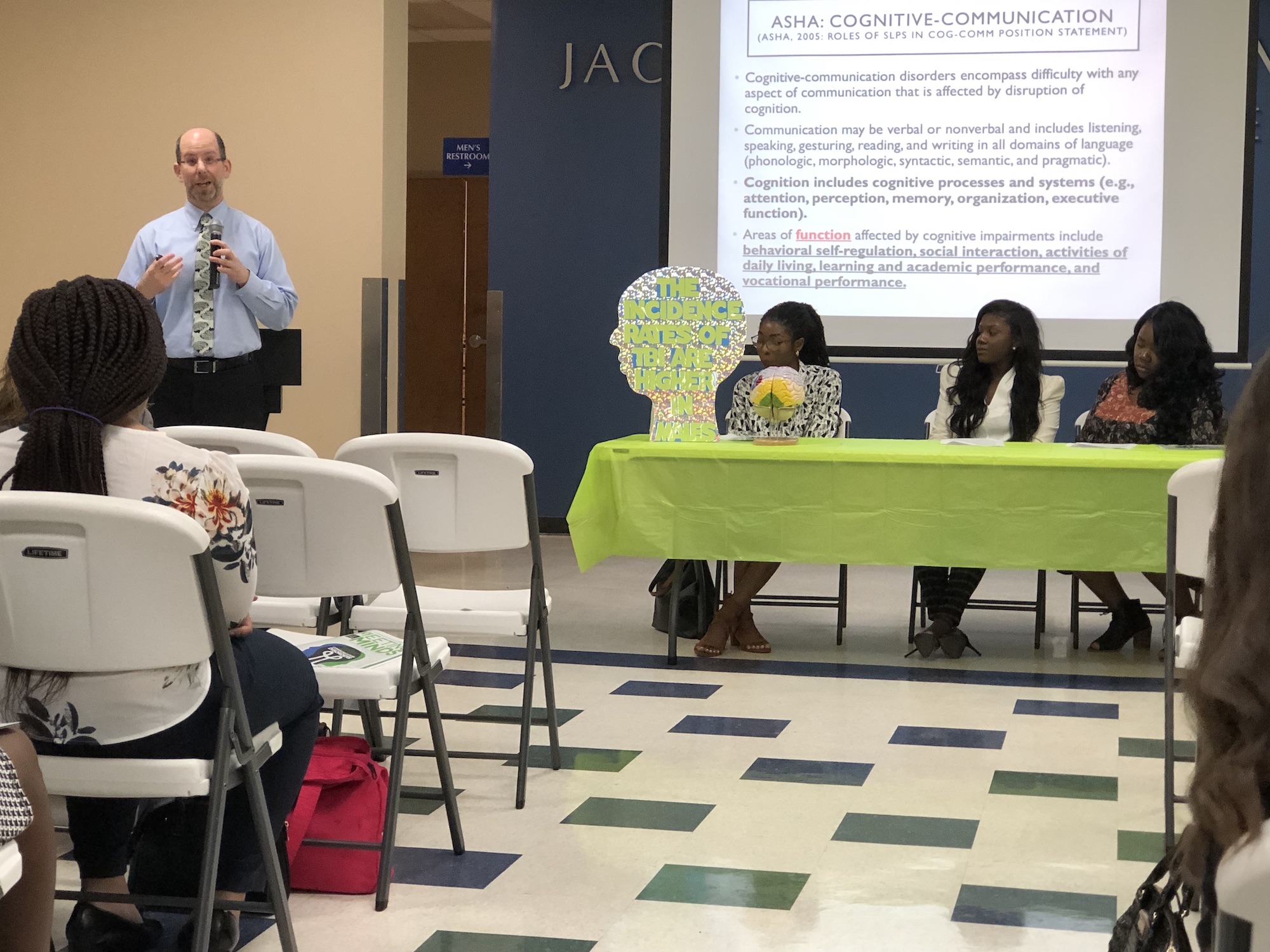

[hr]Living with and caring for those with traumatic brain injury hasn’t gotten a lot of attention in the past, but the impact on individuals from military blasts and professional sports is raising greater awareness, according to an expert at a recent symposium by JSU’s School of Public Health.

Keynote speaker Dr. Rick Lemoncello is an associate professor of Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon. His expertise is in speech-language pathology, occupational therapy and psychology. In addition, he is the program director for Sarah Bellum’s Bakery and Workshop that provides return-to-work opportunities for adults with brain injuries.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]EMONCELLO said there’s now greater discussion about the issue in light of those who suffer from CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), notably football and hockey players.

The forum by the Department of Communicative Disorders titled “A Meeting of the Minds” addressed several current challenges related to rehabilitation, isolation and support.

Lemoncello paints a vivid picture of what patients typically endure within the first 24 hours after suffering a severe brain injury. He said they lapse into a coma with no ability to awaken the brain.

He said as they gradually become alert “it’s not like what you see on TV where they just wake up and start talking, be a little confused and bounce back to life within two days. Instead, it’s a slow process in which they start opening their eyes, interacting with the world, and having some responses.”

Then, he said, patients get into a confused state, not knowing where they are.

“There may be restless, agitative phases of picking at and pulling on things. These represent safety challenges, and some of these clients need to be restrained from pulling out IVs and feeding tubes. It’s a challenging time for clients and family members to see them in restraints, but it’s there to protect the client. Usually the agitative phase is not permanent,” Lemoncello said.

“We tell family that this is a good sign because the brain is slowly waking up and starting to respond to these different irritations on the body, and this is going to pass,” he said.

Lemoncello added that slow progress continues as patients become less confused, more oriented and gradually regains cognitive skills to take control of their lives.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]OWEVER, there are other issues. One involves the apparent indifference of insurance companies by denying cognitive rehabilitation. Often, insurers must be persuaded that a particular therapy works and is medically necessary.

One aspect of that argument is that traumatic brain injury is hard to study because “no two people with brain injuries presents in the same way, so it’s hard to develop a large randomized trial showing the effectiveness of our intervention.”

Lemoncello notes that about six years ago, cognitive rehabilitation was still considered experimental. He said that although Blue Cross Blue Shield changed its attitude about rehab, “it still didn’t say it would pay for it. However, they stopped saying they would flat out deny it.”

Meanwhile, Lemoncello’s work with Sarah Bellum’s Bakery and Workshop provides a different form of therapy. His nonprofit bakery organization helps restore a sense of value and worth to his brain-injured workers, whom he calls bakers and sales representatives.

“Consistent repetition of doing things the same way, every time, day after day will help build those new functions,” Lemoncello said. “The facility provides an outlet for them as a “safe, supportive environment where they can come, feel and experience repeated success. They interact with other peers where they don’t have to explain their brain injury or why they’re having difficulty paying attention or remembering. They can become their own support group as well. It’s about tackling the problems of isolation.”

Lemoncello said, “Oftentimes for that person, hearing from a professional and family member might not always get through, but hearing from a peer going through the same struggles can help them.”

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]TATISTICS already show that less than 50 percent of survivors of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) are employed one year after becoming debilitated. If they were employed at the time of the injury, Lemoncello said there’s a significant increase in the risk and rate of longtime unemployment – three times the rate for females and five times for males.

Dr. Brandi Newkirk-Turner, chair of the Department of Communicative Disorders, said the “Meeting of the Minds” symposium resulted from a generous donor. “The program continues the department’s quest to address topics that matter to people from various disciplines and backgrounds.”

She said the student-centered program also included a service project, “A Race for the Brain Case 5K.” Ultimately, that event raised enough money to make two sizable donations to organizations that support individuals with brain injuries: the Brain Injury Association of Mississippi and Sarah Bellum’s Bakery in Oregon.

A student in the audience said she was enlightened by Lemoncello’s presentation. Brianna Smith is a second-year graduate student at JSU who’s studying to become a speech-language pathologist. Currently, she’s interning at Batson Outpatient Clinic at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, working with children with TBI, speech and language disorders and other rare conditions related to cognitive and alternative communications.

Smith said, “The most inspiring thing about Dr. Lemoncello’s presentation was his drive to combine two things for which he’s passionate – baking and community-oriented rehabilitation post-brain injury. For a while, I’ve been gathering ideas on how I’d like to combine my passion for music with my desire to provide meaningful and unique speech/language intervention for economically disadvantaged and underrepresented children.”

She said she wants people to know that time in the hospital and in rehabilitation doesn’t last forever for all patients after TBI injury. “At some point, they have to return to home, work, school and the community at large. As therapists, our intervention should address these challenges they’ll face as they return.”

Smith said she’s committed to her profession.

“Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are not as popular as the teachers, physical therapists or other professionals we often work alongside. As a constantly evolving field, many people just don’t understand our role and scope of practice. I’ve witnessed firsthand the challenges advocating for children who would benefit from speech-language therapy. But, their parents only see physical therapy, for example, as a priority because their child ‘talks well enough.’ ”

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]HE said it’s important to educate society about the vital skills and assistance provided by speech-language pathologists to those with communicative challenges. “A wide scope of the practice that includes fluency, voice, cognition and swallowing can help parents, potential clients and other professionals know when someone can benefit from our services.”

Overall, Lemoncello said that despite some hurdles and a lack of groundbreaking research, work is underway to improve outcomes of patients living with brain injuries.

He notes successful advances in the use of virtual reality, vision therapy and prism adaptation as a way to help clients rewire the brain.

“There is medication that is showing potential.” He lists options that include hyperbaric oxygen, progesterone therapy and sleep management for concussions.

In future years he said he’d love to see more preventive work so that incidences of traumatic bring injuries decrease. Among these methods would include improvements in helmet safety, along with vehicle navigation systems and sensors to prevent accidents.

Also, another big push would involve changing the medical insurance model so patients get assistance beyond the first six to 12 months after an injury. “Research shows that two, three, five, 10 and 20 years post-injury that folks can still benefit from intensive therapy,” Lemoncello said.

Finally, he urges those who assist people with brain injuries to show more compassion to avoid “a blowup.”

He said an empathetic lens will allow supporters to step back and process rather than becoming angry. “Otherwise, neither one of you will be happy. Remember that this is not the person acting or reacting. It’s the brain injury,” Lemoncello concluded.